India’s government is determined to help Indian smallholder farmers succeed and has numerous programs in place designed to achieve this goal, but it’s running into problems.

The government offers subsidies, insurance, and financing mechanisms to support smallholder farmers. Access is an issue—these programs don’t always reach the intended beneficiaries. Farmers are supplied with fertilizers, but inefficient use lessens the impact of these programs. India’s government monitors weather and soil conditions and takes pains to alert farmers of changes, but oftentimes the information doesn’t arrive quickly enough.

India’s smallholder farmers also fall victim to traders who know market conditions better than they do and undercut the farmers on price. This occurs despite the government’s best efforts to ensure all sides have equal access to market data.

To correct all of this, the Indian government launched the Digital Agriculture Mission (DAM). It’s barely a year old, so it may be too soon to grade this initiative, but DAM’s careful design and bold vision could serve as inspiration for other countries hoping to give their smallholder farmers a leg up.

Building a DAM

The flagship initiative aims to overhaul the country’s smallholder farming economy by digitizing and standardizing information collection and dissemination. The aim is to create a digital architecture for registering and tracking information on farms and farmers. With better knowledge of who is growing what and where, and what type of support they may need, it’s hoped that the government will be in a stronger position to get support directly to the farmers who need it most once this architecture is in place.

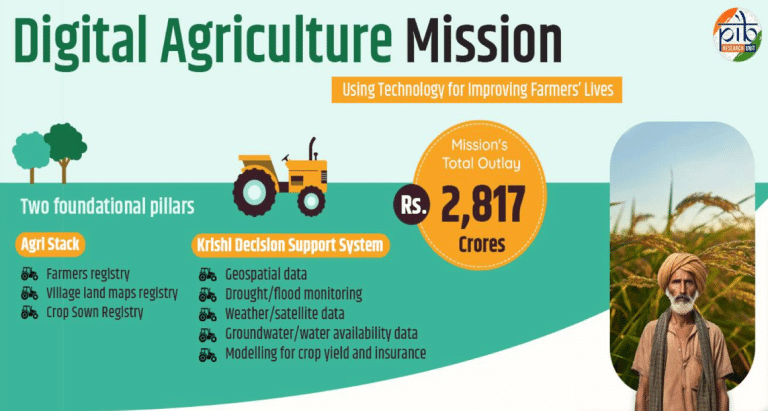

DAM is approved and funded in September 2024. It will be held up by “two foundational pillars,” according to India’s Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare.

AgriStack will form something of the digital foundation for the program. The plan is to build AgriStack with databases comprised of three registries.

Through a Farmers’ Registry, India’s smallholder farmers will be assigned digital identities or a “Farmer ID” that verifies who they are. The thinking is that this will make it easier for farmers to access credit and other financing opportunities. Beyond government support programs, digital verification and tracking will hopefully encourage more private lenders to lend funds to farmers, in turn encouraging more farmers to take advantage of such opportunities.

Next, the government wants to link Farmer IDs to georeferenced maps of farming villages. The plan seems to be to build a sophisticated geographic information systems (GIS) application tying geographic locations to individual farmers and farms, demographic data, and state land records, among other pieces of information.

Finally, AgriStack will house a “Crop Sown Registry” built from data collected in crop surveys conducted annually. As the government explained in a press release issued at the launch of DAM last year, “crops sown by farmers will be recorded through mobile-based ground surveys” so the government can better predict harvests.

With these three parts combined, AgriStack will become a massive trove of farm and farmer data constantly updated, enabling the government to have as clear a picture of the smallholder farming economy as possible.

“The Digital Agriculture Mission is designed as an umbrella scheme to support various digital agriculture initiatives.”

In addition to AgriStack, the government is putting in place the Krishi Decision Support System to be the second main pillar of DAM. This is where the satellites will come in.

“The Krishi Decision Support System (DSS) will integrate remote sensing data on crops, soil, weather, and water resources into a comprehensive geospatial system,” the government explained.

To support AgriStack and Krishi DSS, India will also conduct a Soil Profile Mapping effort. The plan is to create a map of soil conditions and quality covering some 142 million hectares of farmland.

It’s ambitious, but once complete, DAM will arm India’s agricultural authorities with a complete bottom-up and top-down picture of the nation’s smallholder farming economy: on-the-ground registration and tracking, satellite-based sensing and monitoring, and regular monitoring of conditions beneath farmers’ feet.

A graphic from the press release issued in September 2024 by India’s Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare announcing the country’s new Digital Agriculture Mission.

Great progress

Though just a year old, the government has already laid much of the groundwork for building DAM.

Seed funding for the project—approximately $300 million—has been secured. As of mid-August 2025, the government reported that 70 million farmers have been issued Farmer IDs. Pilot digital crop surveys have been completed in a number of Indian states. Officials are on the ground, busy creating soil maps, as well.

Meanwhile, India’s federal government and the state governments are joining forces to build AgriStack and Krishi DSS.

The bottom line is, DAM won’t be found at a single website, office, or center. Rather, what’s envisioned is a network of interconnected tools and systems designed to greatly improve the delivery of government support to smallholder farmers. National government agencies, state governments, nonprofits, and academic research centers will all play a role in DAM’s success.

“The Digital Agriculture Mission is designed as an umbrella scheme to support various digital agriculture initiatives,” as the Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare put it. “These include creating Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), implementing the Digital General Crop Estimation Survey (DGCES), and supporting IT initiatives by the central government, state governments, and academic and research institutions.”

Grow Further will be watching as India builds and implements its Digital Agriculture Mission. We’re excited to see how Indian farming is strengthened with so much detailed information on farmers, farms, crops, soils, land holdings, and regional conditions. It will take a while to be fully formed, but even hints of early success could inspire other governments to make their own investments into digital agricultural information. — Grow Further

Photo credit: Traditional plowing method in Manthralaya, India. Ananth BS, Flickr and Creative Commons (CC Attribution 2.0 Generic).