The World Food Prize, considered the “Nobel Peace Prize for food” in international agricultural development circles, has a new honoree, a specialist in aquaculture, smallholder fish farming, and innovative fish-based foods, and a champion in the fight for better global food security.

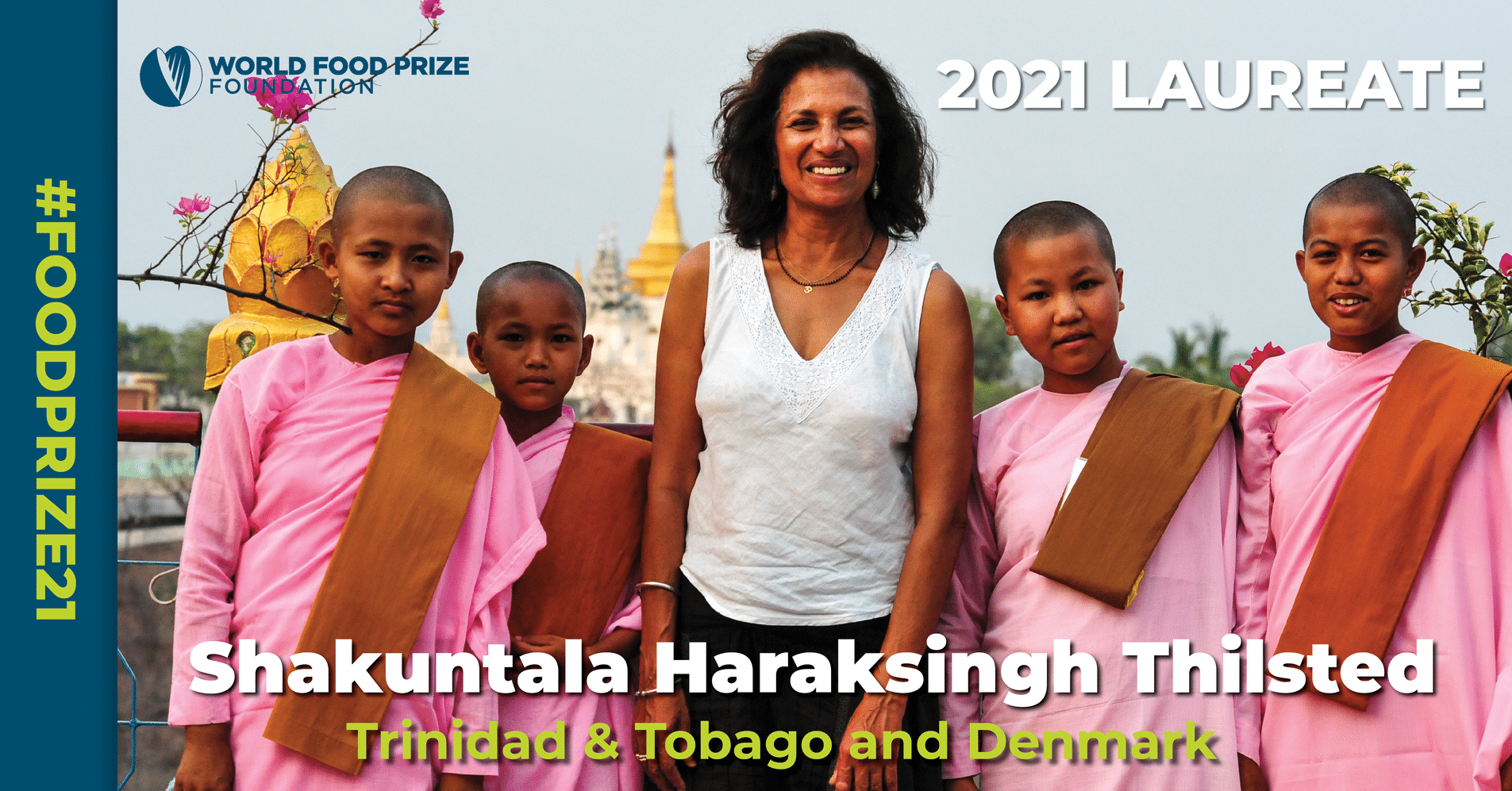

The World Food Prize Foundation announced today that its 2021 honor goes to Dr. Shakuntala Haraksingh Thilsted of Trinidad and Tobago. Dr. Thilsted is renowned for her work on developing and spreading innovative aquacultural techniques designed not only to enhance food quantity but also food quality, the more important factor in her opinion. Barbara Stinson, president of the World Food Prize Foundation, delivered the announcement along with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Thomas Vilsack, World Food Prize Selection Committee Chair Gebisa Ejeta, and United Nations Nutrition chair Naoko Yamamoto during an online ceremony streamed live this morning.

Stinson said Thilsted was selected for her lifelong career in the “transformation of aquatic food systems” to the benefit of women and children in particular. “Dr. Thilsted expanded the evolution of food systems from feeding to nourishing,” Stinson said.

As the 2021 winner, Dr. Thilsted becomes the 51st winner of the World Food Prize, only the seventh woman to be so honored, and the first woman of Asian heritage selected. Thilsted is now bestowed with the distinguished title of World Food Prize laureate and a $250,000 cash prize. “I am truly honored to receive the 2021 World Food Prize,” Thilsted said. “This award is an important recognition of the essential but often overlooked role of fish and aquatic food systems in agricultural research for development.”

Secretaries Blinken and Vilsack both congratulated the winner in pre-recorded messages. Blinken said Dr. Thilsted deserves recognition for her “groundbreaking research into small fish species” and for research that discovered the nutritional richness of small fish species, making these previously neglected protein sources a centerpiece of food security initiatives in Bangladesh and beyond. “Dr. Thilsted figured out how these nutrient-rich small fish can be raised locally and inexpensively,” Blinken said. “Innovations like these transform people’s lives.”

“Congratulations to her and her team,” he added.

Vilsack called Thilsted “a worthy recipient of the World Food Prize this year,” singling out her pioneering techniques of “pond polyculture” that both boosted nutritional outcomes and farmer incomes, but also vastly reduced the use of pesticides in rural fish farming. “She has pioneered fish farming methods that are more productive and environmentally responsible,” he said.

Shakuntala Haraksingh Thilsted was born in Trinidad and Tobago “and raised in a progressive Hindu family” as she put it. Dr. Thilsted said food played a major role in her upbringing thanks to her grandmother. “The kitchen was the beating heart of my childhood,” she said.

Thilsted received her bachelor of science degree from the University of the West Indies in the early 1970s, landing a job in the Ministry of Agriculture, Lands, and Fisheries upon graduation. After serving as an agricultural officer and researcher, Thilsted made her way to Denmark, where she enrolled in the Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, earning her Ph.D. there in 1980. She later served as an assistant and associate professor at that same university while also taking on roles for the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. In 1987 she was appointed as a coordinator at the International Center for Diarrhoeal Disease Research in Dhaka, Bangladesh. It was here where she began the work in food security innovation that would eventually land her the World Food Prize.

Speaking with Agnes Kalibata, special envoy for UN Food Systems Summit, Dr. Thilsted explained how during her professional work in Bangladesh she became determined to not only treat malnutrition but to prevent it as well. As fish was already popularly consumed in Bangladesh at that time, Thilsted said she was inspired to investigate these foods further to see if any potential lay in local aquaculture. She soon discovered that small fish typically neglected in local diets contained “very high levels of multiple essential vitamins and nutrients,” including “vitamin A, B-12, iron, zinc, potassium, essential fatty acids,” critical ingredients in child development. Thilsted called it “our ‘aha’ moment.”

She set out to find ways to grow more of this potentially vital food source in sustainable ways. Thilsted described how she worked to develop pond polyculture systems where fish farmers raise small fish with larger species, eliminating pesticide use in the process. Without the need for pesticides, farmers saved money, and then made more money through producing a higher volume of nutritious fish protein, which was also used to feed farmers\’ families and improve their health in turn. As food production rose, Thilsted found a use for it by developing new products for local consumption, including fish chutneys and fish powder.

Since the 1980s Dr. Thilsted has been working to spread sustainable smallholder aquaculture worldwide, all the while overcoming barriers placed before women in science and leadership. She said she’s been fortunate to be able to overcome these barriers in her professional career, and that she hopes her story inspires other women and girls to follow suit. Thilsted said the lesson learned from her decades of work in food security is clear: “We have the opportunity to make use of all food, land and water systems, more broadly and more holistically,” she said. “Fish and other aquatic foods are an integral part of food production.”

Dr. Thilsted will play a central role at the upcoming UN Food Systems Summit, which Kalibata will lead. “The UN Food Systems Summit is all about changing mindsets,” Thilsted said. “We must have much more research on aquatic foods.”

Last year’s honor went to Dr. Rattan Lal, a United States citizen and professor of soil science at Ohio State University.

Originally from India, Rattan was awarded the Prize for his work on “developing and mainstreaming a soil-centric approach to increasing food production,” per his biography on the Foundation’s website. Lal got his start researching tropical soil erosion and degradation at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture in Nigeria. There, he explored the lack of fertility in many tropical soils. His research revealed how deforestation and excessive tillage under intense tropical conditions led to a massive loss of soil organic carbon, helping to explain in part the failure of the Green Revolution in sub-Saharan Africa—higher-yielding crop varieties developed by Norman Borlaug and colleagues didn\’t have a chance in these nutrient-poor conditions. With this knowledge, Lal helped introduce cover cropping, no-till agriculture, and other methods aimed at keeping plant residues on the surface to allow organic carbon and nutrients to replenish soils. Lal is also credited with explaining the link between soil carbon and climate change. The World Food Prize Foundation says Lal’s lifetime work “promoted innovative soil-saving techniques benefiting the livelihoods of more than 500 million smallholder farmers.”

Grow Further is inspired by the contributions of each of these laureates and seeks to support research that will make similar contributions to global food security.

— Grow Further