Food security isn\’t just about producing enough calories. It\’s also about ensuring that food is nutritious and safe to eat–and preventing the emergence of super-bugs linked to agriculture. Though they’re still struggling to deal with COVID-19, many health experts view anti-microbial resistance (AMR) as the next major global health threat and believe that smallholder farmers are key to the fight against it.

How serious is the threat? Very, according to a panel recently hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Exploring the connections between AMR and climate change, the speakers agreed that the emerging AMR threat is dangerously underestimated by governments and the public. Robert Skov, a science director at the International Center for Antimicrobial Resistance Solutions, said the international health community only began recognizing the severity of the problem about ten years ago as more reports came in from doctors describing dangerous bacterial infections for which virtually no treatment could be found. “Not one single antibiotic is left in the cupboard to treat these,” he said. “Such infections are still rare but they are increasingly there, and it has been estimated that we can go as high as 10 million deaths a year due to AMR in 2050 should we get into this worst-case scenario.” To put that into perspective, COVID-19 claimed over 5 million lives worldwide in two years.

“The use of antibiotics is really speeding everything up.”

Darwin’s dilemma

Evolution explains the problem.

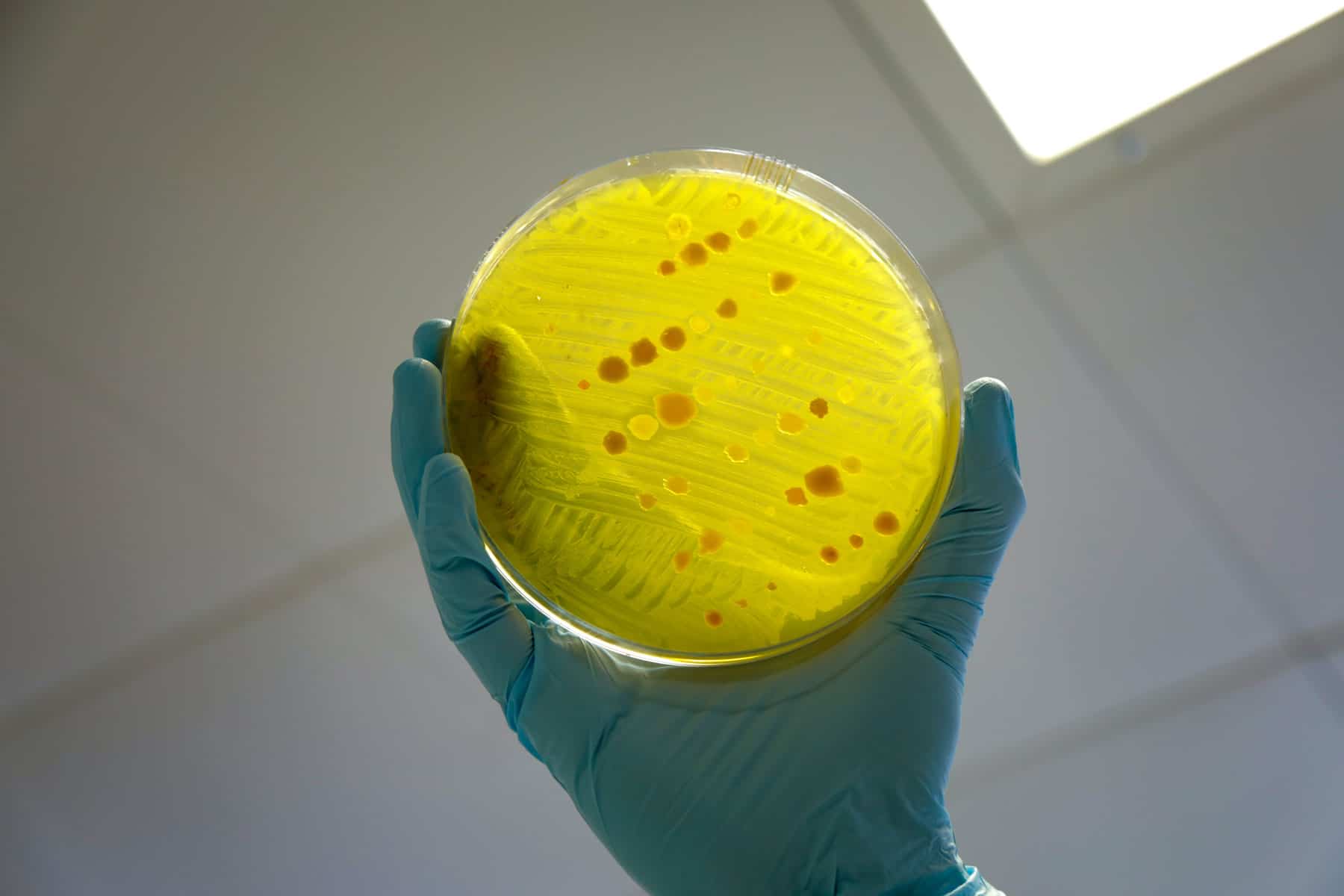

Living organisms, including bacteria, seek to extend their genetic presence on Earth through reproduction. In the process of reproduction, errors occur, known as mutations. Sometimes these mutations are neutral or do not affect an organism\’s ability to survive, and sometimes they are negative and prove detrimental to survival. And sometimes mutations are positive or improve chances of survival according to whatever selection pressures exist in the environment. Through this subtle process, the “fittest” organisms win out and give rise to the next generation, and thus evolution by natural selection gave us the enormous variety of life on Earth. Evolution works very slowly for mammals like us, but very quickly for microbes, on timescales sometimes short as “minutes to days” according to Rod Schoonover, CSIS director of ecological security. Modern medicine treats bacterial infections with antibiotics, which is a good thing. But the overuse of antibiotics by doctors, veterinarians, and farmers is artificially increasing the selection pressure on these bacteria, and in turn, they are evolving resistance to antibiotics at an alarming rate. Bacteria are especially good at evolving quickly because they can share genetic traits among each other and make existing populations more resilient without waiting to give rise to the next generation. “The use of antibiotics is really speeding everything up,” said Skov. “It’s speeding it up in the way that it increases new gain of the systems both from bacteria to bacteria, the horizontal gene transfer, but also the mutation rate.”

“Drug self-administration is common.”

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics

Researchers now know that antibiotic misuse and overuse are rampant in smallholder farms and livestock operations in developing countries. A 2020 study undertaken in Ethiopia discovered that veterinary antibiotics were abundant and readily available for 81% of smallholder livestock farmers surveyed. Farmers use antibiotics frequently and wantonly—about 80% of respondents told the researchers that they often overused antibiotics on their animals and at least 70% knew nothing about proper use (https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2020.00055/full).

Similar findings have emerged from studies on smallholder agriculture and animal health in India and Uganda. India’s smallholder dairy farmers admit to not only using antibiotics liberally on their animals but also on themselves (https://aricjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13756-018-0354-9). CGIAR researchers found antibiotic misuse and overuse common problems at Uganda’s smallholder pig farms, both on animals and humans. “Drug self-administration is common,” they noted, while animals are often treated based on farmer, not veterinarian, evaluations of symptoms. A major factor giving rise to antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, Skov said, is farmers treating healthy animals with antibiotics when the animals don’t need them. Too often antibiotics are administered simply to speed up growth. “That means the animals are not sick, and you give them tiny, tiny bits of antibiotics that don’t kill bacteria but actually accelerate the creation of AMR,” Skov explained at the recent CSIS discussion.

A call to action

Innovations are helping smallholder farmers both grow more food and make the food they grow more nutritious. The above-cited studies and the CSIS panel argue more innovation is now needed to help smallholder farmers raise livestock in ways that keep both animals and people safe from continuously evolving superbugs. The Ethiopian scientists called for “research into the development of usable tools that measure antibiotic knowledge and attitudes” to help combat the threat. The Indian team argued that any solutions must make up for the lack of professional veterinary advice or government guidance in rural smallholder farm settings. Whatever the answers are, the sooner they’re developed, the better. Time is not on our side, and lives are on the line.

— Grow Further